In trying to persuade someone I think there’s a time to argue narrower points and a time to talk about the big picture. Here I went big picture.

I really appreciate the time you’ve taken to engage with me so far. And if you’re willing to go a bit further I think we’d benefit from zooming out to look at the big picture. Because I think that a lot of your concerns are completely valid, and it’s just a question of how they end up fitting alongside other valid concerns.

I agree with you that the world doesn’t owe us anything, let alone a comfortable Western existence. And I agree with you that the comforts in the world are only built with hard work, and freeloading is a very real problem to address. You and I would probably be in complete agreement if we pictured a simple agrarian society where people worked with their hands, everyone worked hard to survive, and some people managed to get wealthier through hard work and good planning. In that case those wealthier people might have no responsibilities to the poorer people in that society, or at least no responsibilities that should involve the government.

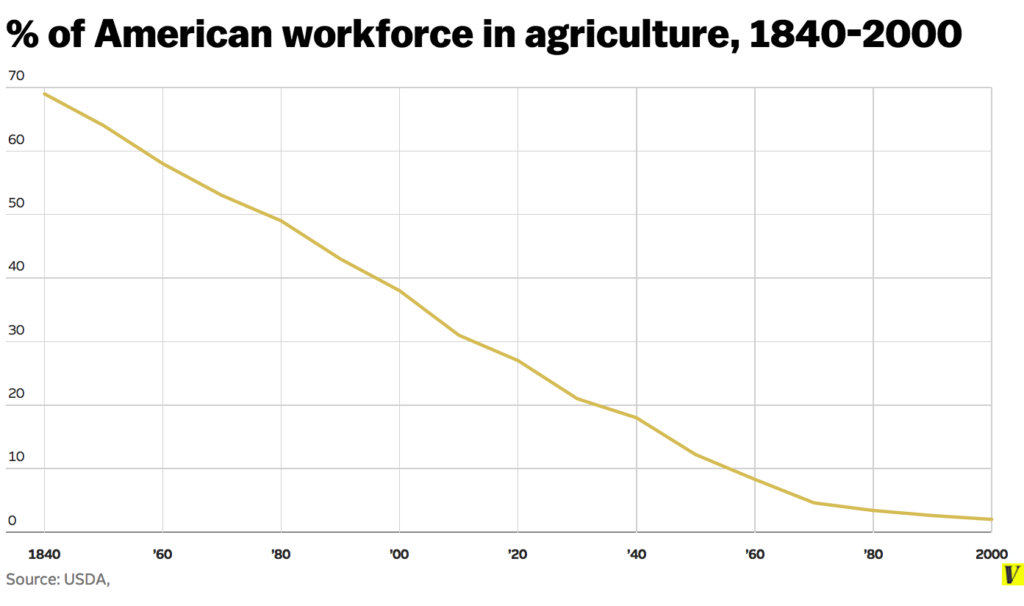

But that’s not the world we live in. About 70% of American workers in 1840 worked on farms, but now just 1.3% do. Today survival is not about working hard tilling your own land but about managing to earn wages within a globalized capitalist economy so that you can then buy the things you need from that economy. Hard work and good planning are still important, sure, but other big factors are also in play. Are you born rich or poor? What kind of schools are you sent to? What wages are available to you when you start working, and how do they compare to the costs of education, rent, childcare, and healthcare? All these pieces have to come together in a way that enables a person to survive. And different government policies can make that harder or easier. And it seems to me that our current policies end up making things unnecessarily hard for folks who are born poor, get sent to terrible schools, and then have to make their way in a world where wages have been stagnant for decades, higher education keeps getting both more necessary and more expensive, and healthcare is not guaranteed and costs twice as much as in other wealthy countries.

Government policies that affect this stuff include minimum wages, how schools are organized and funded, how childcare is organized and funded, whether laws guarantee that workers can take time off when they have children or fall ill, how healthcare is funded, how prescriptions are regulated, how accessible and reliable public transportation is, how zoning and taxes affect the availability and price of housing, whether rents are capped or subsidized, whether laws make it easier or harder for workers to unionize, and what sorts of payments are available to the elderly, the disabled, and the unemployed. Maybe in the end you’ll think it’s still important to prevent lazy people from freeloading, and that’s fine. But we need to understand that issue within its larger context.

Part of that means considering all the different ways that we can cheat one another, and not only how beneficiaries of social welfare programs can cheat. Rich people can cheat just as well as anybody. And when they do, the sums involved can absolutely dwarf all social welfare fraud and freeloading. Tax evasion by the wealthy, for example, exceeds $400 billion per year.

And that’s just one measure of cheating, judged according to our current tax laws. But those laws are not written in stone. Tax laws differ around the world and throughout our own history. From 1932 to 1981 our top income tax rate was at least 63%, and reached as high as 92%. Today it’s only 37%, and lower for investment income. Overall the US collects considerably less in taxes than other wealthy countries do.

Now maybe you think that lower taxes are always better. One worry is that if taxes are too high on top earners that will weaken their incentives, and we’ll ultimately end up with less productivity and less innovation. But the evidence suggests that this is actually backwards. When very high earnings are taxed at high rates this does little if anything to discourage high earners from working. And when that tax revenue is put toward things like education and healthcare the benefits are enormous, both in terms of human well-being and in terms of economic productivity. Better schools produce more productive and higher-earning workers, while universal healthcare and other social supports promote entrepreneurship by lowering its risks.

But I know that for some people it’s more a matter of principle. Social spending is seen as taking away from people who have earned and giving to people who have not. That might be true of cases of fraud and abuse, sure, but I think it’s a confused way of looking at social spending on the whole. Because like I’ve said, earnings aren’t earned in a vacuum. Economic activity is cooperative, and your wages or profits are not some gift from God, but a result of all the economic and legal and financial choices that make up our current system of production and distribution. Together we create goods and services and wealth, and together we decide who ends up getting what. Taxation is simply a way of deciding that the distribution of wealth produced by the rest of the system needs to be adjusted.

Some people argue that such adjustments should never be made. The free market should be left to work its magic, and the government should stay out of the way. This sort of position may sound attractive, and may be right about some of the virtues of markets. But taken to this extreme it’s just not tenable. In the complete absence of taxation and regulation the market produces hellish results, from toxic pollution to child labor to armed conquest. (India was conquered not by the British government but by a British corporation.) Some level of intervention is simply essential. It’s just a question of which interventions are desirable and which are not.

Consider the incomes of different workers before taxes. In theory a worker’s wages will reflect the value that her work contributes, and those getting higher wages will deserve it because of their higher productivity. And this may make sense if we think, for example, of a janitor earning $20k, an assembly line worker earning $40k, and an engineer earning $60k. But the question is how far we can stretch this analysis. In 1989 when the average CEO earned 58 times as much as the average worker, was this justified? Did CEOs really contribute 58 times as much as regular employees? And do CEOs today really contribute 278 times as much as, and deserve 278 times the pay of, an average worker?

We also need to consider those who aren’t earning wages at all. Because as great as the differences are between a worker and a CEO, ultimately both of them are employees working for a wage and selling their labor to somebody else. Those buying the labor are mostly the very small number of very rich people who own things like corporations and patents and factories and machinery. Like the richest 0.1% of Americans who together own more than the bottom 80% do.

There’s a basic conflict between those owners and us workers. When they buy our labor they’d always prefer to pay as little as possible, and of course we’d prefer the opposite. Part of how things play out is through supply and demand and the price mechanism, but that’s not the whole story. Another part is the immense power differential between us and them. They’re the ones who fund campaigns and lobby legislatures and own media companies. And what’s at stake for us is paying rent and buying groceries to survive, while they’re only playing a financial game to further increase their wealth. And in case of serious labor disputes they’re the ones who can call in men with guns.

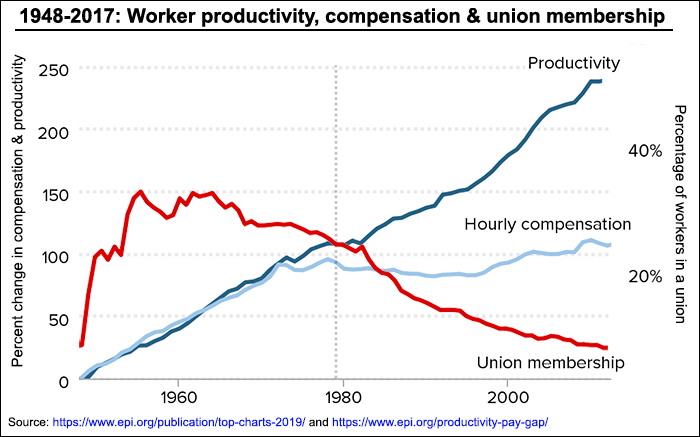

A crucial way for workers to gain leverage here is to unionize. But federal laws, regulations, and enforcement practices have a big impact on how easily workers can form unions and how effectively unions can bargain. Today about 10% of American workers belong to a union, while in 1945 it was over 33%. And the decline in union membership seems to track pretty neatly the way that wages have stagnated even though worker productivity has continued to climb. It seems that owners have just had enough power to capture all that new value for themselves.

We also need to consider how businesses can capture value they don’t create. As businesses compete in the market they’re relying on things like roads, airports, drinkable water, breathable air, public schools, teachers, firefighters, police, and soldiers. When these conditions enable some businesses to make huge profits I’d say that we taxpayers deserve a return on our investment.

What’s the alternative? Are we really supposed to think that Jeff Bezos created $200 billion in wealth all by himself? I say that since we pay to educate his workers and protect his property and create the conditions where he can do business, he owes us.

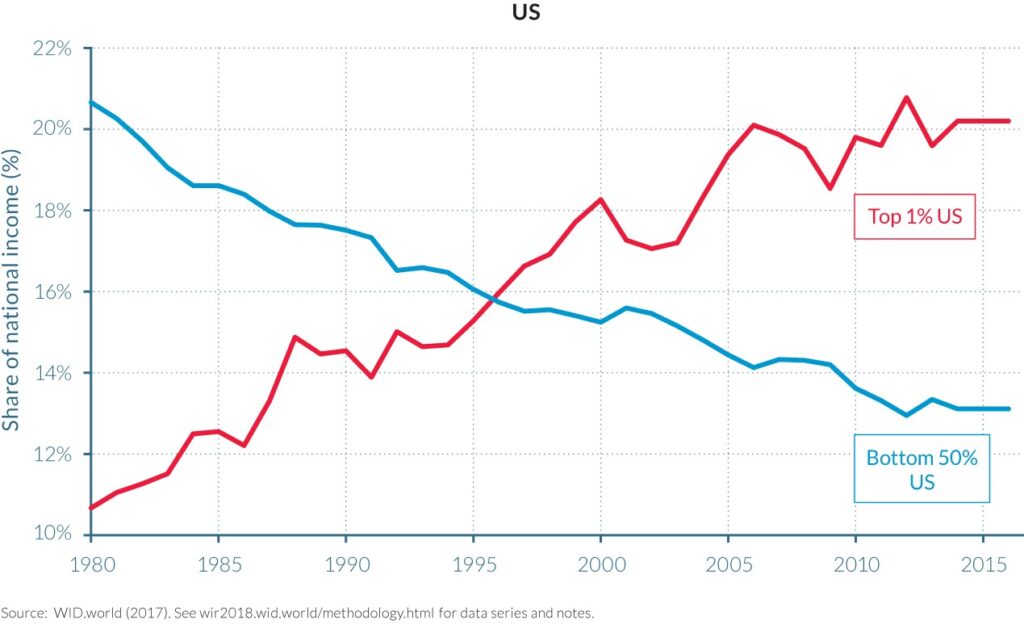

And we have to consider what giant fortunes like his mean more generally. The richest 1% of Americans own more wealth than the bottom 90%, including owning half of the stock market. The richest 5% own two thirds of the country’s wealth. Inequality in America has been increasing for decades and is now more extreme than it’s been since the eve of the Great Depression. The richest 1% own 40% of all wealth, which is twice what’s owned by the richest 1% in the UK, France, or Canada.

So the richest Americans are mind-bogglingly rich. But they are taxed at what are historically and globally low rates, while public infrastructure crumbles and poor and working people struggle without the access to essentials like healthcare and education that’s guaranteed in other rich countries. Is this really an ideal system? It may be more ruthless than other systems at keeping lazy people from freeloading. But it also makes millions of hard-working people unnecessarily miserable, and condemns to economic failure millions who would have succeeded with just a little more help.

I know you’re proud of the sacrifices that you personally made to succeed. But I think we have to be careful when applying that sort of pride to questions of public policy. I think it’s possible to take pride in your own accomplishments without taking any pleasure in the sufferings of people who don’t share them. And when we’re thinking seriously about politics I think we should be more concerned with lessening suffering where we can than with preserving some particular sufferings that we think are deserved.

Maybe there’s a worry that if things get too easy and safe then the whole system will fall apart. Without the sticks and carrots of extreme poverty and extreme wealth things won’t function. But this worry is misplaced. Plenty of incentives for hard work remain if the richest make millions instead of billions, and the poorest sleep in public housing instead of public parks. Higher taxes and a stronger safety net don’t cause the skies to fall. Instead in countries around the world they produce economies that compete with ours, while having less inequality, more social mobility, and more people able to live in dignity and security.

Does any of this hit home? Have I made an initial case that maybe yes, there are some ways we can improve our current system, and they have more to do with levying fair taxes on the rich than with judging and policing the poor? Or is there something you think I’m missing?